D-Day+80. Lest we forget.

For the 80th anniversary of D-Day, I am reposting what I wrote five years ago on the 75th, which itself reprised my coverage of the 50th anniversary for The Washington Post and a subsequent solemn visit my wife Sandy and I made to the site in July 2009. At a time when democracy is threatened both at home and abroad, it’s important to recall a time when Allied forces fought back and ultimately triumphed over the evils of hate and the Holocaust perpetrated by an authoritarian regime that sought to rule the world. But, lest we forget, the fight for freedom must be won over and over again.

In 1994, I had the honor and privilege of telling the story of the D-Day landing through the voices of veterans, then mostly in their seventies. Years later, in July 2009., Sandy and I visited Omaha Beach — now a public family vacation spot — and the American cemetery, with its countless rows of crosses and Stars of David. There was absolute silence, befitting this mass graveyard of thousands of young men who died on the beach below us. We solemnly placed stones on the graves of the Jewish soldiers and also thought sadly of the rest marked by crosses. They were all so young. Sandy remarked that many were born the same year as her father, 1921.

On this, the 75th anniversary of that fateful landing, I’m offering the text of the Washington Post story I wrote (and some photos I took in 2009). Long before “Saving Private Ryan,” it brought home to me the

horror, tragedy and bravery of that day. I hope it does for you, too.

horror, tragedy and bravery of that day. I hope it does for you, too.

“They Survived a Beach Called Omaha,” which ran in the Washington Post on May 30, 1994.

Here’s the text:

What they remember most is the chaos – units landing in the wrong place, their guns and tanks sunk at sea, and unexpectedly severe firing from the high bluffs above.

And on the beach, no cover. The bombers had dropped their payloads inland instead of on the beach to create craters for hiding. At first, the Navy guns also were misdirected. And in the water and on the beach, the waves of soldiers kept coming and kept dying.

“The beach was strewn with dead and dying and equipment,” remembers William Friedman, 77, a retired Army lieutenant colonel who lives in Northwest Washington.

“It looked like all the debris in the world had been gathered up and thrown on that beach.”

It was both the highest and lowest point of their lives. It was a time best remembered and best forgotten. It was D–Day, the largest amphibious invasion in military history, the Normandy landing that skirted disaster, the one they survived to tell about.

For the 50th anniversary, some are going back one last time, to commemorate the battle they won and memorialize the comrades they lost. Others, hobbled by the infirmities of age or disinclined to dwell on the traumas of war, are staying home.

They are men who have lived almost a lifetime since June 6, 1944 – men such as Jim Lipinski, of Alexandria, who married a Holocaust survivor of a labor camp he helped liberate and remained in the Army an additional 17 years; Frank Bowen, of Rockville, who helped rehabilitate soldiers in a military hospital in England, fought in the Korean War and later had a career with IBM; and John Finke, of Fort Belvoir, who stayed in Germany during the occupation and worked for the Office of Strategic Services, forerunner of the CIA.

Yet for most, the passage of time and the intervening events have not dimmed the memories of Omaha Beach.

“At Omaha Beach in the morning, it was as bad as combat has ever been,” historian Stephen E. Ambrose says. “You had companies taking 96 percent casualties in five minutes. The volume of lead and steel coming down on the men of Omaha was certainly as much as Pickett’s men faced at Gettysburg.”

A large share of those troops came from Maryland and Virginia. The assault on Omaha consisted of soldiers from two infantry divisions: the 29th, formed from units of the Maryland and Virginia National Guard, supplemented by draftees from all over the country and untested in battle; and the 1st, veterans of the North African and Sicily campaigns.

The combined force of 35,000 would suffer about 3,000 casualties that day, including more than 2,000 dead.

By D–Day plus 11, the Allies had 487,643 men and 89,728 vehicles ashore, achieving the dramatic success that historians have described as the beginning of the end for Hitler’s Third Reich.

But the men who landed at Omaha on the first day remember an invasion that had all the markings of failure.

Friedman’s outfit, the 1st Division’s 16th Regiment command unit, landed roughly on schedule at 8:15 a.m., but not “where we were supposed to. Worst of all, we didn’t know we were going to meet opposition. Our intelligence showed us coming in on an unoccupied beach … with resistance inland.”

Because of the fire from the beach, landing craft ramps were lowered as much as 100 yards off shore in water sometimes neck-deep. Laden with rifles, packs and grenades, men “went down plumb to bottom if slightly wounded,” their equipment sinking to the bottom, Friedman recalls.

“When we landed … there was no movement at all. We were all just exposed, under intense fire, clear observation. The tide was pushing us onto the beach, and the beach was mined. Talk about the true meaning of being between the devil and the deep blue sea; this was it. I was in a mass of human bodies, dead, alive, wounded.”

Lipinski, now 72, was the regimental warrant officer. Of the 102 men crowded onto his landing craft, 35 were killed before they reached the beach.

The landing craft faced a German machine gun nest “raining a hailstorm on the front ramp before the ramp was even lowered,” Lipinski says. “I got away from it because I went over the side and not over the ramp.”

It was low tide, and Lipinski waded to a sand dune in front of the beach and crouched behind it. There he found three others from his company.

“I started them over the dune one at a time,” he says. “Then I went over, and all three of them were lying dead on the other side.”

Whatever could go wrong did, it seemed. Arthur Van Cook, 75, a Bronx native who now lives in Springfield, was a lieutenant with the 29th Division’s 111th Field Artillery Battalion, which was supposed to provide support for the 116th Infantry. It took three boats to get him to shore. The first amphibious craft sank as it came off the landing ship; a second one also went down. By then, there was almost no artillery left.

“My battalion had the distinction, if you can call it that, of landing without any guns,” he says. “All our field artillery pieces were sunk, out in the water, gone, except one.”

They did what they could with what they had. As the veterans tell it, leaderless men from different units found each other and fought together on the beach. In some cases, commanding officers remained with their units and issued memorable send-offs.

“There are two kinds of people on this beach,” Friedman remembers his regiment’s commander, Col. George Taylor, saying, “those who are dead and those who are going to die. Move in and die.”

Finke, 83, a captain and rifle company commander in the 16th Regiment who now lives in an Army retirement community at Fort Belvoir, had broken his ankle in England three or four days before D–Day. But he hid his injury so he could be part of the invasion.

He rode in the lead landing craft with a bandaged ankle and a cane, then used the cane to prod his men past the mined pilings and other obstacles that lay between the water and the beach.

“If I hadn’t gone ashore, 200 soldiers would’ve disappeared because they didn’t want to go to shore,” he says. “I hit ’em in the ass, kicked ’em in the ass. I was just their old man.” Later that day, a mortar shell broke his elbow and ripped his leg, his fourth wound of the war.

Van Cook remembers that when he informed his commanding officer there were no artillery pieces, he was ordered to round up as many artillerymen as he could find on the beach and tell them to use their rifles and bayonets instead.

What finally saved the day, more than one veteran says, was the Navy. Misdirected at first, the Navy guns offshore eventually found their targets, the German gun emplacements on the cliffs.

Recalls Van Cook: “Some battleships out there firing 16-inch guns … did a number on those {German guns} looking right at us. If not for those birds, we might still be there.”

By late afternoon, Van Cook says, “you had 155-millimeter howitzers coming in and the tanks. You had to get the hell off that beach or get run over by your own stuff.”

Erman T. Clay came over two days later.

In those days of racial segregation in the armed forces, the D–Day assault troops were all white (although some Native Americans were in the first wave of parachutists to land in Normandy).

Clay, 71, who grew up on the Potomac in Southern Maryland and now lives in Northeast Washington, had been drafted into the 1st Division’s all-black 544th Quartermaster Battalion.

His job in England had been to waterproof vehicles for the landing.

On the way to Normandy, his ship was bombed and strafed but for the most part unharmed. By then, enough land mines had been removed for the troops to follow a four-foot path across the beach.

“On each side, all you could see was dead men stacked up like cordwood,” he says. “They would bring us in, take a load of them back. Your first thought is you want to get in and do bodily harm to the folks who killed your soldiers.”

But that wasn’t his job. Instead, Clay and his company unloaded trucks, stacked ammunition, guarded prisoners of war.

“We’d see these other units coming in, going on to the front,” he recalls. “We felt we needed to be a part of that. But it didn’t stop us from doing the job we were doing.”

The war ended. They came home, raised families, pursued careers in and out of the military.

Most were eager to put the war behind them, to marry, to get an education, a postwar house, a piece of peacetime America – the dream for which they’d fought. They did not talk about the war much, they say, or about D–Day. There was a reticence, almost an unspoken understanding that the horrors of D–Day were best left behind on Omaha Beach.

Long after D–Day, Lipinski gave his son copies of his Silver Star recommendation and a report about his landing craft, “but he didn’t seem to follow up with questions… . We’ve never talked about it. Mostly, I talked with other soldiers.

“My personal memories, I must have put them out of my mind” until the recent focus on the 50th anniversary, Lipinski says. “I sort of blacked out the whole Omaha Beach. I suspect a lot have.”

For some veterans, the whole 80-day Normandy campaign has become something of a blur. Robert T. Cuff, 83, of Ashton, who was in the 29th Division, isn’t sure which day he landed in Normandy. What he recalls is that “we were just a target for the Germans on the hill. … They fired at us all the way to the Elbe River.”

Bowen, a captain who commanded Company C of the 115th Regiment, thinks mostly about the narrow escapes, like the shell that landed seven feet away when he was standing on the bluffs above the beach. It gave him a bad concussion, but it killed the sergeant standing next to him and severed the body of one of his other men.

“It was something I won’t be forgetting as long as I’m able to think,” says Bowen, 81, who was wounded by machine gun fire six days later. But, he adds, “I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about it.”

“We felt fear, and then we didn’t feel,” Friedman says, recalling the long ascent up ravines from the beach to the bluffs. “We were emotionally drained when we got to the top of that hill.”

Most of the veterans do not express deep thoughts about D–Day‘s historic significance or how the combat affected them. It’s enough, they suggest, to say this: They survived, and many didn’t. For their own survival, they give thanks; for those who didn’t make it, they mourn still, and perhaps even more so now that all eyes are again focused on the beaches of Normandy.

Several thousand American veterans of World War II will be going there this week to commemorate the invasion. The 29th Division Association is returning en masse: A total of 485 people, including 230 Normandy veterans, have chartered 10 buses for a full week of scheduled events. First Division veterans are going back in smaller groups.

Clay, who worked for the Veterans Administration and the Treasury Department after the war, returned with his family on the 25th anniversary. When he looked at the beach again, he says, he was even more struck by the odds the troops faced. “I couldn’t see how it was possible for us to get in, with all the ammo and pillboxes and 88s the Germans had,” he says.

Lipinski has never gone back to Normandy and isn’t going this year. “I just never had any desire to,” he says. “One time was enough for me.”

Van Cook has been back to Europe many times, but never to Normandy. “I always pictured it full of rubble and bodies,” he says, “and I didn’t need to go back to see that.” But he is going back for the 50th, figuring that he won’t get another opportunity.

So is Friedman. “I think this is sort of a last chance at nostalgia,” Friedman says. “Things like the beach tie you together, you know. We realize fully this is really rather the last hurrah.”

Copyright The Washington Post Company May 30, 1994

+++

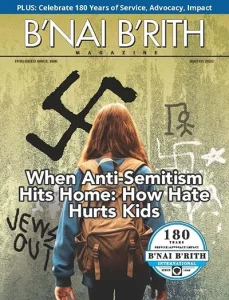

As if to remind us that the struggle continues, the 2023 cover story of B’nai B’rith Magazine, which I’ve been honored to edit since 2009, was “When Anti-Semitism Hits Home: How Hate Hurts Kids,” by Beryl Lieff Benderly. It’s a story I wish we didn’t have to publish. But publish we did, and now, recognizing its importance, the American Jewish Press Association has awarded the magazine a first-place “Award for Excellent in Writing about Young People/Families.”

Lovely…thank you for sharing. Never forget the past!

If you wrote the same piece today you would be asked to find people who do not live in the Washington area to give their accounts. The Post is now an international publication with little use for the thousands of readers living in the DC area. It meant so much to me reading this piece again that the story was told by “neighbors.” I know where they lived in 1994. Maybe our paths had crossed. One was 72, my age next year. It haunts me to think these guys are all dead now. You brought them back to life. In my LOCAL newspaper.

It haunts me

“It haunts me” should be deleted.

Not sure I can edit your post. But it haunts me, too.