Birthright Citizenship: It’s Personal

My grandparents were immigrants. My parents were both born in this country and thereby became “birthright citizens,” a right affirmed by the 14th amendment to the Constitution enacted in 1868 and repeatedly upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. Now comes #47, who signed an executive order the evening of his inauguration seeking to abrogate the Constitution he swore to uphold, defend and protect against all enemies foreign and domestic.

Already, 22 states have filed legal challenges to this arguably illegal order. Under Trump, this long settled issue has suddenly become unsettled, as he rails against the undocumented immigrants he also plans to deport, along with their American-born children.

After some time, my grandparents became “naturalized” citizens, but not before their American-born children achieved birthright citizenship. In our time, efforts to provide a path to citizenship for 11 million undocumented residents have been repeatedly thwarted. A bipartisan bill to address immigration issues seemed on its way to passage until Donald Trump during his out-of-office interregnum ordered it killed. But rather than address the problem, he found it more useful to use the “crisis at the border” against his then presumed challenger in his reelection campaign. His new 700-word executive order takes away the long established birthright citizenship of anyone with undocumented parents who is born starting 30 days from its issuance.

At the root of this attempted reversal of a bedrock principle in our country is less about porous borders than about prejudice against “others.” The origins of this order are not hard to find. They are grounded in Project 2025, the rightwing prescription to remake America. Though birthright citizenship is not specifically mentioned, its strongest adherents were major contributors to the document.

The Statue of Liberty, a sculptured lady in New York Harbor welcoming the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” including my ancestors, must be weeping. Her sentiments seem almost quaint in today’s America. But you don’t have to dig deep into our past to see a different, more welcoming country.

America welcomed my paternal grandparents and their then three children from Germany in 1886; there would be five more born here, including my grandmother, Rose Previn, whose son Gerard, born in 1909, was my father One of her brothers enlisted in the American Expeditionary Force in World War I and emerged decorated but shell-shocked. America also welcomed my maternal grandparents, my grandfather in 1904, leaving behind his wife, my grandmother, and their three-year old daughter in a small town in what is now Belarus. My grandmother Rochel Lampert, who became Rose in this country, arrived in 1907 with the child born as Basia but who I would know as Aunt Bessie. A year later, in 1908, my mother Emma Lampert was the first to be born in America, in a Lower East Side tenement. She was followed by three others, a sister and two brothers who served in the Army and Navy World War II.

If my parents had not had “birthright citizenship,” it is unlikely that either I or my sister would be here, much less as Americans who took their citizenship for granted. That is not even to mention the exclusionary laws this country has enacted, to keep out Chinese (1882) and Eastern and Southern Europeans, through restrictive quota system adopted in 1924 to stop the influx of immigrants (Italians, Jews) nativists here deemed undesirable.

For a time, the Second World War seemed to awaken the nation’s conscience to the plight of those seeking refuge from oppression and worse at the hands of fascist regimes. Though antisemites in the State Department did what they could to undermine efforts to rescue victims of the Holocaust, the popular ethic had changed, so that those fleeing Nazism were portrayed positively in Hollywood films and in society in general. “Americanization” for a time replaced “America First” as the prevailing sentiment in the land. The goal was not only to welcome refugees but to assimilate them into our national life.

Yet, even then, it was not a given. In November 1940, Gerhart Hans Saenger, a German-born psychologist and educator, published an essay in The Journal of Educational Sociology, on “Assimilation and the Minority Problem.” He wrote:

“Our troubled times have left only rare spots where a person is taken for what he is, welcomed with all his peculiarities, his religious and his national characteristics. Elsewhere, wherever we turn, we hear the cry for national, racial, or cultural unity. The demand of the hour is to conform or to die….Those who happen to be different in their language, the color of their skin, the form of their heads, in their behavior, or religion are taken as potential or real enemies…”

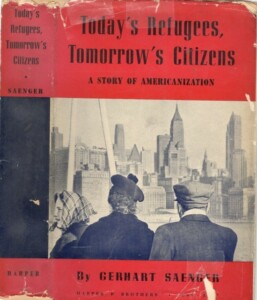

Saenger didn’t stop there. In 1941, he published a book, Today’s Refugees, Tomorrow’s Citizens: A Story of Americanization. He was “in exile from his native land,” social worker and adult educator Eduard C. Lindeman wrote in a foreword. “Many of the immigrants have endured persecutions perhaps unparalleled in the history of modern mankind,” Saenger wrote in his introduction. He then began his book with a short item from the Feb. 22, 1940 New York Times reporting on the docking of the U.S. Liner Manhattan with 535 passengers, including 270 German refugees.

“For most of us,” he wrote, “this is a small item in our daily newspaper. For those 270 refugees, however, it marks a decisive point in their lives, a new beginning. Behind them lies terror and the flight from countries which were for centuries their homes.”

The Kokomo Tribune praised Saenger’s book in an “Americanization” editorial on June 16, 1941. “What made all these millions ‘suffer a sea change’ when they crossed Atlantic or Pacific or border and became Americans?” it asked. “It was perhaps largely the fact that they came voluntarily to a land of freedom and opportunity… Or perhaps the form of government under which they lived and the Constitution on which it rested affected them. At any rate, a miracle that has been repeated so steadily for 321 years ought to be trusted to continue along the same line, given half a chance to do so.”

Although the 14th amendment was adopted primarily to assure the rights of formerly enslaved African Americans and their children, reversing the 1857 Dred Scott decision that even free blacks could not be citizens, its birthright citizenship clause has had a much wider impact. Consider that the ancestors of many millions of Americans today — even Trump supporters — came here for opportunity or to flee oppression or poverty. Whether or not they came here legally or illegally but later obtained legal status is beside the point. If their offspring had not been accorded birthright citizenship, neither they nor their children and grandchildren would now enjoy the benefits, bounty and privileges of America. And how much different and poorer this country would be.

Well said, well written. . . . Well done, Gene-O.

Such an eloquent and profound message, Gene. Thank you!!!

Hi Gene. The undocumented immigrants who are otherwise law abiding are only guilty of the Federal misdemeanor of crossing the border without permission. The punishment for conviction of this crime is expulsion. Thus, Biden could have pardoned them and legally blocked Herr Trumpf from his vile project. Jimmy Carter z’l did it for 500,000 draft evaders, so it can be done. Frightened of the ugly xenophobic blowback, Biden and the Democratic leadership have left them defenseless. I contacted reprentatives and Senators and major media figures over the last few weeks beseeching them to lean on Biden to act. Only Michael Moore responded publicly. From my perspective, Biden is a coward. You guys should come over for dinner soon.

Could be my story too…. Just substituting some Polish & Lithuanian names: paternal grandmother Anna Gromney who married grandfather Walter Plachta & maternal grandparents Valeria & Peter Vareika. Finally visited Ellis Island last summer to see where they arrived before settling in upstate New York & a small Massachusetts town.