Becoming Kay Graham

In February 1970, through a combination of persistence and luck, I came to work at the Washington Post. It so happened that my name is the same as the man who bought the paper at a bankruptcy sale in 1933. Eugene Meyer was a prominent banker, Federal Reserve chairman and the father of Katharine Graham, the subject of a new documentary “Becoming Katharine Graham” now streaming on Prime. Harry Rosenfeld, the Metro editor who hired me and, despite his key role in the Watergate story, was left out of the documentary, wrote in his memoir about this odd name coincidence.

“As we continued the search for new talent, a couple of job seekers stood out,” he wrote. “When Eugene L. Meyer applied, I could not resist hiring him because he bore the same name, aside from the middle initial, as Katharine’s father. Thankfully, Eugene Meyer had bona fide credentials and went on to perform as a reliable member of the staff. Word came down to me that Mrs. Graham was not overcome with glee, not appreciating the humor in it as much as I did.” More bluntly, at a book signing at the Newseum in fall 2013, Harry told me, “I took a lot of shit for hiring you,” he told me. “You did the right thing,” I assured him.

I first met “Kay” (as my older colleagues always referred to her) in the Post‘s old L Street building. “One local reporter’s byline gave Mrs. Graham a start,” wrote chief diplomatic correspondent Chalmers Roberts in his 1977 centennial book The Washington Post: The First 100 Years. “When she encountered him in an elevator, she introduced herself and asked ‘Don’t you have a middle initial?”” I did. My byline had always been Eugene L. Meyer. And, according to my recollection, I first introduced myself to her, not the other way around, to gales of laughter from my fellow travelers in the elevator.

I suppose in a weird celestial way I was fated to come to the Post. When I was 13 years old, the New York Times ran a story with the headline: “EUGENE MEYER, 80, IS HONORED BY 800.” And during the summer before my senior year in high school, my namesake died, aged 83, and the Times headline was “$10,000,000 LEFT BY EUGENE MEYER.” Both of these items had absolutely nothing to do with me. Nonetheless, I kept them folded up in my wallet.

After my surprise reincarnation at the newspaper of my namesake, from time to time confusion reigned. Though the “other” Eugene Meyer was long gone by then, he continued to receive mail, which invariably was routed to me. Thus, I amassed a collection of Christmas cards, several years worth, from Bob and Dolores Hope. At the other end of the economic spectrum, I would receive repeated requests for help with circulation problems from an elderly woman in Southeast Washington. She even enclosed a check, which I dutifully sent upstairs to the office of Kay’s son Don, who would succeed her as publisher.

Talk about name recognition! For nearly my entire tenure of 34 years at the newspaper, Don and I had a running joke. He would greet me, “Grandfather!” or sometimes “Grandpop!,” and I would return the favor, greeting him, “Grandson!”

Oldtimers in the newsroom felt compelled to tell me Eugene Meyer stories. One ancient (or so he seemed to me) copy editor delighted in relating how the late publisher would stroll into the newsroom evenings to ask “Are there any news tonight?” regarding “news” as the plural form of “new,” to which the copy editor would reply, “No, Mr. Meyer, there are no news.” So, one Saturday night, I strode up to the desk, posed the question and got the stock answer, but with a postscript: “Mr. Meyer also gave out dollar cigars.” Then the deskman added, sympathetically, “You got a helluva reputation to live up to.”

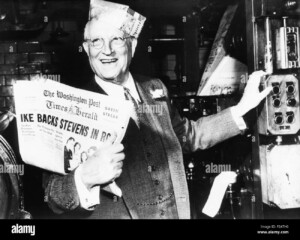

Eugene Meyer displays copy of The Washington Post after acquiring the Times-Herald in 1954.

What emerged from such anecdotes was the universal regard and affection in which he was held. In one photograph, he is wearing a newspaper folded up on his head, a printer’s hat, and in fact, he was made an honorary member of the International Typographical Union. He was also revered for sharing the paper’s profits by giving shares of stock in the 1950s to many longtime employees who subsequently retired as multi-millionaires as a result. His daughter Kay would much later be reviled by the unions as anti-labor, a union buster, and, as the Newspaper Guild Unit Chair, occasionally when I wanted to needle management, I would forgo the informal “Gene Meyer” tagline in my bulletins for the more formal “Eugene Meyer.”

Many outside the paper shared this illusion. When I was addressing groups of native Washingtonians of a certain age, my opening line was, “Good evening. My name is Eugene Meyer, and I do not own the Washington Post. I just work there.” It was a statement of fact that always generated laughter.

When the film version of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s Watergate book “All the President’s Men” premiered at the Kennedy Center in April 1976, everyone in the Post newsroom had a free ticket. But unlike almost everyone else on the staff, who were directed to balcony seats, we were in the orchestra, fourth row center, surrounded by luminaries such as syndicated columnists Art Buchwald and Bob Novak. My wife and I quietly took our seats and enjoyed the show.

Among the many themes in “Becoming Katharine Graham” was her shyness and her fear of public speaking. Somehow, there was a time when I came to her rescue. Don was supposed to give a talk to the Charles County, Maryland Chamber of Commerce but for some reason couldn’t make it, so Kay (or if you will Mrs. Graham) was to be his replacement. As Mr. Maryland at the Post, I received an urgent phone call one day from her office. Could I come downtown to meet with Mrs. Graham and help her prepare for the event? Soon enough I entered her seventh floor office with a map of the state, in order to acquaint her with the geography.

Unfolding and spreading it out before her I said, “Of course you know that Charles County is next to Prince George’s,” which is next to the District of Columbia. “No,” she replied in her upper crust manner of speaking, “I didn’t know that.” Here she had grown up in the nation’s capital where she lived in a large mansion and on the family’s huge estate in Mount Kisco, Westchester County, New York, but, to borrow a line from “The Music Man,” she didn’t know the territory.

My next advice was this: You will be addressing the Charles County chamber, but the dinner will be at a hotel in Clinton, in southern Prince George’s. So do not say how happy you are to be in Charles County, because you won’t be.

There followed a flurry of faxes between her office and mine to craft her talk. At long last, the evening she dreaded had arrived. I went there with Milton Coleman, who rose to Deputy Managing Editor before retiring. We went to see her before the talk, and she was extremely nervous , terrified really, and so lacking in self-confidence, not the strong female CEO the world now knew who had shown her mettle throughout the heights and depths of Watergate, who had stood by her reporters and editors through almost unimaginable presidential threats.

But on this weeknight in an unfancy hotel in a mostly obscure corner of Southern Maryland, Katharine Graham hit it out of the park.

Postscript

Don Graham and I had more than a casual joking relationship through the years. We had several sidebar meetings for breakfast and dinner in an attempt to settle a contract between the paper and the Newspaper Guild in the late 1970s. He and I came to what I still believe was a good deal for the unit’s several hundred editorial and commercial employees. But my committee, at the recommendation of our chief negotiator, an old union warhorse, turned it down. Ultimately, we settled for much less, a far worse agreement that was a watershed contract for the newspaper industry at the long-term expense of its workers. But that outcome did not affect my positive feelings towards Don, who became famous for sending handwritten notes to reporters over stories he especially liked. They became known as “Donniegrams,” and I’m proud to have received a few, which I still have. But the one I perhaps most cherish is the one Don wrote responding to my condolence card I sent him upon Katharine Graham’s death in 2001. I cannot recall what I wrote but here is what he wrote back:

Dear Gene,

I am very, very late in

writing, but wanted to thank

you for the especially thoughtful card

you sent me at the time of my mother’s death.

It gives me a chance, too

rarely taken, to say how much

I have enjoyed working with you,

ever since we were city reporters together

in 1971.

Don

“You got a hellova reputation to live up to,” the old copy editor had teased me over my name’s the same. I certainly cannot claim that I did, but Don Graham, who knew everyone by name at the Post where he began unassumingly after serving in Vietnam and a stint as a D.C. cop, did his best to do so.

Recalling Selma sixty years later

March 1965 was calm in Washington, where I worked as the bureau librarian for the old New York Herald Tribune, reading, clipping and filing seven newspapers a day. But there was violence in the South, as civil rights marchers crossing the Edmund Pettis Bridge in Selma, Alabama were attacked by hose-wielding police and K-9 dogs. I had never marched for or against anything, and now, as an aspiring journalist, I was reluctant to start. But the stark images out of Selma are horrendous and horrifying. So, on a lunch break, I joined the picket line in front of the White House to protest this manifest evil. I took only a couple of turns in the line before heading back to the bureau at 1750 Pennsylvania Avenue. But I had dared to cross a line of neutrality in my profession, and it is not an action I was inclined to repeat–until the November 1969 Moratorium to end the war in Vietnam. But that is another story for another time.