“The future of New York is Queens.”

“The future of New York is Queens.”

— Gary Shteyngart, New York Times, Dec. 28, 2025

And now, a pause from current events for a bit of personal nostalgia from the past, from a time when the country was united in a righteous cause to fight and defeat fascism.

PART I

Jackson Heights, Queens

Actually, my past in New York was Queens. In Jackson Heights, Queens, to be precise.

Early in my young life, my parents rented a one-bedroom apartment at 89th Street and 35th Avenue in Jackson Heights. It was during the war (WWII, the only one still referred to as “the war”), and one of my early memories is of a blanket covering the kitchen window so that enemy aircraft would not see that there were occupants in apartment 3G. Our apartment was north facing with an alley view. On either side of the alley were single family homes.

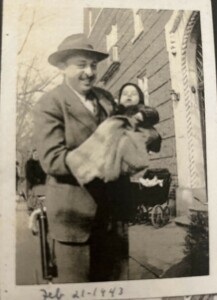

When I listened to the radio shows, Superman was one of my favorites, and I was convinced I could don a cape and jump from the kitchen window. I don’t recall if the window was nailed shut to prevent that from happening, but maybe. 35th Avenue was a wide street (by definition, avenues always are), and I remember when the war in Europe ended in May 1945 watching V-E parade from a neighbor’s apartment that faced the avenue. I have somewhere in the family archives a picture of myself at aged three wearing a one-piece “V for Victory” suit.

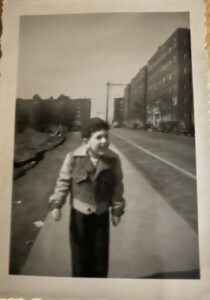

Another picture shows me proudly wearing an Eisenhower jacket on a street corner in the vicinity. I think these were all the rage among patriotic preschoolers then. I was an adventurous little kid. One time I broke out of nursery school, climbing over a chain link fence to freedom. Newly empowered, I wandered around Jackson Heights, Queens, two blocks up to Northern Boulevard, before finding my way back to the apartment building and my frantic parents. On another escape, I saw firemen fighting a blaze and back in the apartment drew a picture of what I’d witnessed, an early clue, my mother later said, that I was destined to be a reporter.

PART II

Jackson Heights, Queens, back in the 1940s did not look that different from now. Eighty-second street was and is the main business strip. The elevated train still rumbles over Roosevelt Avenue, where passengers ascend and descend many steps to and from the platform. Just south of the elevated my mother’s cousin Jack Pearl the family’s dentist had his office, one stairway above 82nd Street. He was said to have been captured by the Germans during the Battle of the Bulge in the winter of 1944 but managed to escape and came home a war hero He made the New York papers. It’s not something he ever shared with me; it’s just part of my family’s lore.

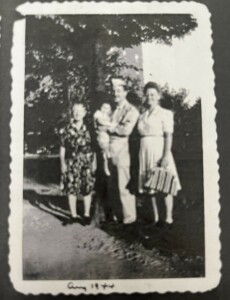

My mother’s brothers, Bernie and Harry Lampert, were, respectively, in the Navy and Army. I cherish photos of them in uniform with my proud grandmother, whom we called Bubby, outside our Jackson Heights apartment. Bernie was stationed on a ship in the East River, guarding Manhattan from the Bronx, he joked. Bernie was then sent to Falmouth, England, where he remained for the duration. Sgt. Harry Lampert was deployed to Drew Field, in Florida, where he drew cartoons for the base newspaper. In 1940, before the war, he’d drawn the first Flash comic book, which much later in his life made him a huge celebrity, indeed an icon among fans of the Golden Age of comics, as well as a featured speaker Comicon conventions.

My father, Gerard Previn Meyer, registered for the draft but was not initially called up. My parents almost named me “Justin,” because I was born just in time to keep him, a married man with a child, at home. But then, motivated by his own sense of patriotism, he volunteered for the New York City Patrol Corps, known as “LaGuardia’s Army,” to guard the home front, including the nearby airport. Below is a photograph, very likely taken inside the Jackson Heights, Queens apartment, of my dad in his uniform, my mother gazing lovingly and proudly at him. She balked at pistol training, ending my dad’s service. But he felt self conscious on the subway when he heard others in uniform ask what was his unit. He then sought a military commission, citing German as his “ancestral language,” but burying the lede below a recitation of his many academic honors in English and French literature.

When deferments ended for men married-with-children, he was drafted during the Battle of the Bulge. By then he was 35 years old and, at the last minute, after he’d had his going away party, his draft order was rescinded due to his age. By then, he was teaching at nearby Corona Junior High School. Sheepishly, he returned to the classroom to find someone had scrawled on the blackboard “Mr. Meyer is dead.”

Loved your article. Brought back memories of living in Brooklyn during the War. Dressed in Red Cross clothes collected money for the War Effort. Living near the ocean men patrolled the streets making sure lights were out. Listened toThe Shadow Knows for escape and fantasy.