Morton Mintz, R.I.P. and Washington Post Buyouts Then and Now

My friend Mort Mintz died this week at 103. Fittingly, the Washington Post, where we were colleagues for many years, gave him a nice obit, starting on the Metro news front and filling columns inside. It was decent enough, but incomplete.

Mort broke into newspapers in St. Louis in 1946 and worked at the Washington Post from 1958 until he retired in 1988. His national reputation as a top-flight investigative reporter came from his work exposing the Dalkon shield and thalidomide, the drug that doctors were prescribing as a sedative and tranquilizer for pregnant women who then gave birth to babies with physical deformities.

He never won a Pulitzer but did receive the coveted George Polk award for his work. He was also honored with the Heywood Broun Memorial Award and chaired the Fund for Investigative Journalism. And he inspired generations of reporters to follow in his path.

Mort’s strength was his bottomless pit of outrage, though some considered it a flaw. He was, in the view of newsroom management, a pain in the butt. He would slave over his reporting and writing, the latter needing editing but so what? His stories didn’t always immediately see the light of print. Instead, they were sometimes held for days, or weeks, or longer.

In those days before everything was computerized, “printers” were real people who took hard copy and converted words into “hot type” letters and sentences on linotype machines. The type set in wood boxes were then used by “compositors,” another lost trade, to create frames and pages that rolled on the presses to produce the newspaper. Stories that didn’t run right away were left to languish in “overset.”

Due to delays in his stories getting published, the joke in the newsroom was that his autobiography would be titled “Morton Mintz: My Life in Overset.”

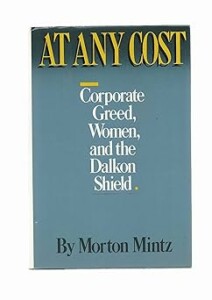

But Mort’s sense of outrage wasn’t just over delays in publishing his work. Unregulated corporations inspired him to take on corporate powers and complicit politicians in the auto, medical and tobacco industries. In the course of which he produced several important books, including “Power, Inc. — Public and Private Rulers and How to Make them Accountable,” co-authored with Jerry S. Cohen, and “At Any Cost: Corporate Greed, Women, and the Dalkon Shield.” I cherish the books he inscribed to me full of praise without a whiff of self-importance “for Gene with (damn near) unbounded respect and admiration…” But that just mirrored my feelings towards him.

Did I mention that he was also a dedicated and stalwart member of The Newspaper Guild? When the pressmen’s union struck the Post on Oct. 1, 1975, Mort was, like many of us, torn between his unionist sympathies and his loyalty to the readers and to the publisher Katharine Graham, who he called Kay, as did others of his generation. The pressmen had not gone out peacefully, setting presses aflame and beating up a pressroom foreman. Mort was among many, including myself, who worked during the strike, though he then chose not to and joined the pressmen’s picket line.

In the midst of all this, our own contract expired, the guild local filed charges against those crossing the picket line, and a company union sprang up to challenge guild representation. Legions from the newsroom quit the guild, but not Mort. The “Washington Newspaper Union” lost the election, barely, but it was a pyrrhic victory. In the ashes, I somehow rose, if that’s the right word, to become the Post Guild’s Unit Chair while we were still without a contract.

In that role, I published 52 bulletins in 1978. They included a three-part series conceived and written by Mort. Based on the Post’s public filings with the SEC on executive compensation and the company’s bottom line, they exposed the poor-mouthing hypocrisy of management. I titled the series “The Fruits of Your Labor.” (There was also a Part IV written by Larry Kramer, who went on to become a newspaper publisher in San Francisco.) i can’t say that these bulletins alone moved management to settle, but I like to think that Mort’s deep dive into company finances were not for naught, and the series is still occasionally cited. Eventually, we settled a contract, though not a good one, whose negative clauses affected generations of “unborn” workers.

After Mort retired from the Post, he did not leave his outrage at the door. Nor his strong commitment to helping others, including those close to him. When his beloved wife Anita’s health declined, he was her primary caregiver. They had moved from their longtime home in Cleveland Park, where they’d raised four children, to an apartment in Foggy Bottom.

Twice a year, I’d see Mort at an authors dinner at Old Europe, the venerable German restaurant on Wisconsin Avenue north of Georgetown, organized by mobologist Dan Moldea. One time, standing together in the chow line, Mort casually mentioned that he’d been at D-Day as a young naval officer commanding a landing craft that took soldiers to Omaha Beach in Normandy. He’d never mentioned it.

Another time, a group of us were standing around chatting, and someone asked Mort what he was writing these days. “Checks” was his one-word reply. Mort was then well into his 90s and still driving. When the dinner ended, I along with the late Barry Sussman, Woodward and Bernstein’s Watergate editor who was written out of the film “All the President’s Men,” escorted Mort across Wisconsin Avenue to his vehicle. Miraculously, he got home safely.

Some two years later, on September 7, 2018, I met Mort for lunch. Using a walker, he managed to travel the block from his residence to The River Inn hotel restaurant at 924 25th Street NW, and then back. Twenty years after he’d left the Post, he was still angry at Kay Graham and Ben Bradlee, both by then deceased. Despite his major contributions to investigative journalism and to the Post, and his kindness to colleagues, he still felt underappreciated by the newspaper. He’d never gotten the merit raises he deeply deserved, given by management to talented reporters who were more easily managed.

Time to let it go, I urged him. But he would not. Time does not always heal all wounds.

Especially in these times, it seems important to still get outraged, to pay attention and become angry. Let that be an important lesson and no small part of the legacy of Mort Mintz.

Buyouts, then and now

In January 2004, I was one of 56 Washington Post employees to benefit from the first newsroom-wide buyout in the paper’s history, out of 69 total employees in Guild-covered jobs. The generous buyout was followed by a memorable tribute and celebration in the New Community Room on the ground floor of the building at 1150 15th Street NW. Each of us was given a facsimile front page from his or her first day of employment at the Post; mine was Monday, Jan. 23, 1970 — a Guild holiday, as it turned out, earning me extra pay.

“Behind every great newspaper are heroes… big and small,” read the inscription on the printed invitation for for the Feb. 18, 2004 newsroom retirement party. Chairman Don Graham “also reminded the attendees that many of the retirees were unsung heroes whose commitment to the Post made the newspaper great,” according to an account in Shop Talk, the house newsletter. The Guild honored us, too, at a separate reception a month later, at the the legendary Post Pub, around the d corner at 1422 L Street NW, a treasured watering hole for Post employees that no longer exists.

There had been no pressure to leave, but our financial planners said I could not afford not to take it, so I did, and the years since have been fulfilling, personally and professionally, as I freelanced for magazines and newspapers and other publications, published two books (and am working on a third), edited a magazine, started this blog, and raised three great sons with my spouse and life partner Sandy Pearlman.

Shortly before I left, an op ed column appeared (“End of a Year and, Maybe, an Era”) by Mike Getler, then the Post’s ombudsman, a position long since abolished, even before the paper was sold to Amazon billionaire Jeff Bezos.

It was a “good time,” wrote Getler, a former Post editor and foreign correspondent, “to take a break from the complaint business. Better at such times to think about people and things that affect our daily lives.” Those accepting the buyout, Getler wrote, were “a group with a thousand years of cumulative4 journalistic experience… some well known bylines are among them,” he wrote naming names of even lesser lights, including me “and photographers whose names appear in small print but whose pictures are big…”

Fast forward 21 years — the age of maturity, it was once called. The Washington Post under Bezos, seeking not only to downsize its staff but seemingly to downgrade it in the eyes of many Post subscribers, offered a less generous buyout and a less endearing parting message to the takers. Publisher Will Lewis, the former UK editor tied to a Murdoch-enabled hacking scandal, suggested in an email to staff that those “not aligned” with the paper’s turn to the right should go. The deadline: July 31. As of this writing, it appears that more than 100 newsroom reporters, editors, photographers, and opinion writers got the message and took the buyout bait.

This has outraged Gene Weingarten, a brilliant former editor in the Post’s Style section who now and then handled my copy. In his SubStack column, he “unpacked” the Lewis memo to make clear its message to staff: “If you are currently a principled journalist working for The Post, a person who values integrity, we don’t want you here anymore, whining about what we are doing…” Echoing Getler, he continued, “In losing these people, The Post has not just squandered much of their top talent — they are losing all institutional memory.”

For those pondering their future under this “voluntary separation program,” Weingarten offered to translate Lewis’ lofty-sounding and transparently insincere corporate rhetoric thusly: “If you choose to move away from The Post, thank you for all your contributions, and I truly wish you the best of luck,” which he translated to mean “Go fuck yourself. Leave.” This time, it appeared, there would be no warm sendoff for the soon-to-be ex-Posties.

The long list of departing names has been widely published elsewhere, so no need to repeat them here. But so far, it’s safe to say, there will be no hail, no heartfelt farewell coming from the downsized and, at least in its opinion pages, rightsized Washington Post. In my 34 years there, the Post was never quite Camelot, but in the heady world of newspapers, it sometimes came damn close, and now it’s not even distantly close. Are you outraged yet?

Gene, I am so very sorry for your lost of a good friend. Sometimes I think that it’s gods gift to remove the professionals so they don’t have to watch the destruction of the profession they represented and loved so much.

…and yes I am outraged too!

The Post described herein is why I believe it to be the classic American newspaper before the current evolved product. While I began my career in news, delivering the dominant Evening Star at the age of ten, the day was never complete for decades without devouring much of the content of each day’s edition of the Post as the Star faded away.

Gene’s recitation of his experiences provides me with an excellent background, which wasn’t evident or available to the reader of the paper on the inside workings.

Appreciating the outrage of Mr. Mintz is a reminder that if a paper does not embrace outrage, its readers are at the mercy of the good old boys.

While I still subscribe online, it is only for research, as there is little point in reading the predictable reports now published.

I send my condolences, Gene. A good friend is hard to lose at any age, and it sounds like the world is poorer for his passing. Thank you, too, for giving us context on the buyout. I, too, am outraged by the corruption and injustice all around us.

Nice tribute, Gene. . . . God bless, Mort.

Wonderful tribute to Mort and the newspaper business, Gene. I used Mort’s reporting in my book about Helen Taussig. His work and her discoveries in Europe actually tying thalidomide to birth defects pushed public opinion and Congress toward passing tough new laws to test drugs for safety BEFORE giving them out to patients in doctors’ offices, as was the custom. Hard to believe it now. Patricia

Keepp onn working, greaat job!