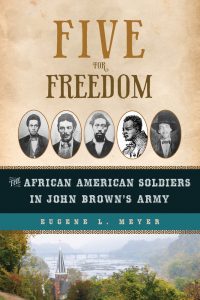

Dangerfield and Harriet Newby: Hidden Figures No More

In my book FIVE FOR FREEDOM: The African Americans in John Brown’s Army, I highlight the tragic love story of Harriet and Dangerfield Newby with a chapter titled “One Bright Hope.”

Dangerfield Newby, born enslaved, later emancipated when his white father and enslaved mother moved to the free state of Ohio, had an enduring union and as many as seven children with Harriet, a woman enslaved by a Dr. Lewis Jennings in Prince William County, Virginia. In need of money, Jennings planned to sell her and their children “down the river,” separating the family and consigning them to the cotton plantations of Louisiana, where life was much harsher.

Dangerfield was negotiating with Jennings to purchase them, but, for whatever reason, the deal fell through. Desperate to save his family, Dangerfield signed on with John Brown, who planned to attack Harper’s Ferry, seize its federal arsenal and rifle works and incite a slave insurrection. The plan was doomed to fail, but in the spring and summer of 1859, hope sprang eternal. Dangerfield, at 39, was the oldest among the five African Americans who went with Brown to the Ferry.

On three occasions, on April 11, April 22, and August 16, 1859, Harriet wrote to Dangerfield, addressing him as “Dear Husband” and signing “Your Affectionate Wife.” In each, she sounded more desperate, writing to Dangerfield that he was her “one bright hope.”

In the first, Harriet reported that “Mrs. gennings,” her master’s wife, had been sick after giving birth to a baby girl. Harriet has had to stay with her “day and night.” Their own children were all well, she wrote. “I want to see you very much…Oh, Dear Dangerfield, come this fall without fail, money or no money. I want to see you so much. That is one bright hope I have before me.”

Harriett received a letter back on April 22 and responded the same day: “Dear Dangerfield, you cannot imagine how much I want to see you. Com as soon as you can, for nothing would give more pleasure than to see you. It is the grates Comfort I have is thinking of the promist time when you will be here. Oh, that bless hour when I shall see you once more.”

Finally, on Aug. 16, Harriet wrote again, right after hearing from Dangerfield: “It is said Master is in want of money. If so, I know not what time he may sell me, an then all my bright hops of the futer are blasted, for their has ben one bright hope to cheer me in all my troubles, that is to be with you, for if I thought I should never see you, this earth would have no charms for me. Do all you Can for me, witch I have no doubt you will. I want to see you so much.”

And with added urgency, she wrote: “I want you to buy me as soon as possible, for if you do not get me some body else will…their has ben one bright hope to cheer me in all my troubles that is to be with you…”

Dangerfield, who’d received the letters in Astabula County, Ohio, would carry them with him to the farmhouse five miles from Harper’s Ferry, where Brown’s tiny army would assemble and prepare for the futile assault on Harper’s Ferry. Dangerfield would ask Brown when he could reply. “Soon, Dangerfield, soon, ” he was told. He could still hope, but only misery–and death–lay ahead.

On Monday, Oct. 17, 1859, a sniper fatally shot Dangerfield as he was crossing an open area in the lower town. Then, for souvenirs, enraged citizens cut off his ears and left him for the hogs. Months later, Harriet and children were sold South. They would return after the war with her second husband and settle in Fairfax County. Descendants still live in the area.

But Harriet and Dangerfield Newby were truly “hidden figures,” to borrow the title of the best-selling book by Margot Lee Shetterly about Black women who were NASA pioneers. The National Museum of African American History and Culture contained one small plaque, in a section about enslaved families being torn apart, with Harriet’s message to Dangerfield that he was her “one bright hope,” but without context. In talks about FIVE FOR FREEDOM, I repeatedly lamented this.

Now, I am happy to report, Dangerfield and Harriet Newby will be memorialized within a year on a state highway marker in the Piedmont region of Virginia, where Dangerfield was born and raised and where Harriet was enslaved. They are among a small number of largely forgotten African Americans nominated by Virginia elementary school children and selected by state officials to receive this long overdue recognition for their historic roles. To watch the Governor’s Black History Historical Marker Contest 2021 Student Celebration, held virtually on April 21, click here.

Four fourth grade students at Kings Glen Elementary School, in Springfield, Va., nominated Dangerfield and Harriet Newby for this honor, as part of the 2021 Black History Month K-12 Historical Marker Contest. As of this writing, the plaque will simply say: “Dangerfield Newby, who was born enslaved in Virginia and later lived free in Ohio, was killed in John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry as he fought to free his wife, Harriet, and their children from slavery.”

Congratulations to the four students at Kings Glen Elementary for memorializing the Newby family so others will learn yet another tragic story of how enslaved people suffered in so many ways.

Dear Gene,

Such meaningful news. You have worked hard to bring the story of Dangerfield and Harriet Newby forward.

It is my honor to have participated in your search. We will always remember “leaving Elvira behind.”

Good story, Gene.

Terrific result of your hard work telling the story of these five brave Americans.