Shields Green: He Went with the Old Man

“I think I’ll go with the old man.” With these words, on Aug. 21, 1859, Shields Green sealed his fate.

The “old man” was John Brown, and Green was a Black man, said to have escaped from slavery in Charleston, South Carolina, who Brown wanted to join his revolutionary army. Leading his small band of men, including five African Amercans, he intended to attack the town of Harper’s Ferry, seize its federal arsenal and armory and rifle works, and incite a slave insurrection to topple the hated institution of slavery.

Green was with Frederick Douglass, who had escaped slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore to become the most prominent Back abolitionist. They had met in Rochester, where Douglass lived and published his abolitionist newspaper. Green was a clothes cleaner by trade and gave Douglass’s address as his own. His business card carried his nickname “Emperor,” as he was said to be a direct descendant of African royalty.

It was in Douglass’s home where Green first met Brown. When he was trying to recruit the abolitionist leader to his cause, he asked that Green accompany him to an abandoned quarry on the outskirts of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Brown was hoping that such a high-profile person as Douglass would join up and he asked that Douglass bring Brown with him.

“Shields Green was not one to shrink from hardships or dangers,” Douglass wrote years later. “He was a man of few words, and his speech was singularly broken; but his courage and self-respect made him quite a dignified character.”

They spent a hot summer weekend discussing Brown’s bold plan. But Douglass thought it more foolhardy than audacious. Brown was “going into a perfect steel-trap,” he warned him, “and that once in he would never get out alive.” As he was preparing to leave, he turned to Green and asked him what he wanted to do, to which Green, as Douglass recalled, gave his fateful answer: “I b’leve I’ll go wid de old man.”

And go with the old man Green did, along with 17 other men that comprised the raiding party on the damp night of Oct. 16, 1859. The town, arsenal and rifle works factory were quickly seized, but soon the plan began to unravel. It ended in the morning of Oct. 18 when 90 marines under the command of Col. Robert E. Lee arrived on the scene.

By that time, Green had passed up another opportunity to escape with two other raiders, Osborne Perry Anderson, and Albert Hazlett, choosing instead to “go with the old man.” Brown, with some of his men—now including Green—and a few hostages had retreated to the arsenal fire engine house. The marines stormed the building and took Brown, Green and others prisoner.

Green, at 23 the youngest of the raiders, would be indicted, tried and convicted by a Charlestown jury, comprised of white slaveholders, and sentenced to death by the judge, also a slaveholder. On Dec. 16, 1859, “Emperor” was executed by hanging from the gallows, alongside John Anthony Copeland, from Oberlin, Ohio. In 1860, the town included his name on a monument to Copeland and Lewis Leary, another Black raider from Oberlin.

The Medical College of Virginia, in nearby Winchester, claimed the bodies of Copeland and Green for dissection. During the ensuing war, Union troops burned the college to the ground.

In 1867, a Maine Baptist named John Storer founded a college for formerly enslaved on Camp Hill, overlooking Harper’s Ferry. The college bore his name, and in 1881, on its 14th anniversary, Frederick Douglass was the featured commencement speaker. He extolled John Brown at length, but he also had high praise for Shields Green “who had attested his love of liberty by escaping from slavery” and joining the raid to end slavery. Should any monument be erected at Harper’s Ferry to Brown, he said, the name of Shields Green should “have a conspicuous place upon it.”.

That never happened, though there is a small plaque off High Street in the lower town of Harper’s Ferry listing all the raiders’ names, with an asterisk next to the Black men, including Green. Black veterans of World War I paid another tribute to him when in 1929 they founded the Green-Copeland American Legion Post 63 in Charlestown (now Charles Town), West Virginia. It no longer exists.

In Harper’s Ferry, an obelisk memorializing Brown was erected on railroad property in 1909, and on October 10, 1931, a memorial tablet was dedicated in the lower town to another Black man. His name was Haywood Shepherd, a free man who commuted to his job from nearby Winchester. He was the hapless baggage handler shot by Brown’s men as he sought to return to the station house on the night of the raid. He was the raid’s first fatality, and his memorial, originally conceived to honor loyal slaves, was placed there by the United Daughters of the Confederacy.

So, 164 years after he decided to go with the old man, ultimately to his death, there is still no monument to Shields Green in Harper’s Ferry. But, as with his martyred captain, his soul goes marching on.

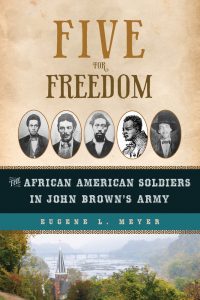

Read more about Shields Green, Frederick Douglass and John Brown in “Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army.”