In February 1859, A Fateful Meeting on the Road to Harpers Ferry

February looms large in the story of Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army, my contribution to the canon of the famous abolitionist who led 18 raiders to Harpers Ferry in October 1859 in an attempt to incite a slave insurrection and abolish slavery.

The five African Americans who joined the raid were Osborne Perry Anderson, John Anthony Copeland, Shields Green, Lewis Leary, and Dangerfield Newby. Only Anderson would survive and write the only insider account of the raid. Each man is profiled in FFF. Four were free men of color, and the fifth, Green, was believed to be a fugitive slave about whom less is known.

Shields Green

But what is known and documented is that Green, from Charleston, South Carolina, reportedly working as a sailor, boarded a ship presumed to carry cotton that took him north. His escape route eventually brought him to the home of Frederick Douglass in Rochester, New York. There he lived for several months, a self-employed clothes cleaner who claimed to be descended from African royalty, and called himself “Emperor.” “Clothes cleaning” announced his business card:

“The Undersigned would respectfully announce that he is prepared to do clothes cleaning in the manner to suit the most fastidious, and on cheaper terms than anyone else. Orders left at my establishment, No. 2 Spring Street, first door west of Exchange Street, will be promoptly attended to. I make no promises that I am unable to perform. All kinds of Cloths, Silks, Satins, &c., can be cleaned at this establishment.”

Another house guest was Brown, who had known Douglass for eleven years. There, in February 1858, Brown met Green. The audacious but doomed raid was still far in the future, but there in the home of perhaps the most prominent Black abolitionist of the century, Brown revealed his preliminary plan.

Douglass later wrote, “While at my house, John Brown made the acquaintance of a colored man who called himself by different names — sometimes ‘Emperor,’ at other times, ‘Shields Green.’ …He was a fugitive slave, who had made his escape from Charleston; a state from which a slave found it no easy matter to run away. But Shields Green was not one to shrink from hardships or dangers. He was a man of few words, and his speech was singularly broken; but his courage and self-respect made him quite a dignified character. John Brown saw at once what ‘stuff’ Green was made of, and confided to him his plans and purposes. Green easily believed in Brown, and promised to go with him whenever he should be ready to move.”

The details were to come, but the course was set to free slaves. Three months later, Brown convened a conference in Chatham, Ontario, to adopt a constitution for the free state he hoped to establish in the Appalachian mountains of Virginia, from which guerilla war would be waged on the plantations below. Neither Douglass nor Shields were present.

His plans were postponed after they somehow got out, unnerving his New England backers who were patrician white abolitionists. But by the following summer, they were on again. Brown needed a high-profile Black leader and sought to recruit Douglass to join him. He asked Douglass to meet him in August 1859 and, specifically, to bring Green with him. They came together at an abandoned quarry outside Chambersburg, Pennsylvania over a weekend in August 1859.

Douglass demurred, warning Brown he would be walking into a “perfect steel trap” from which he would never emerge alive. As he was about to leave, Douglass turned to Green and asked him what he wanted to do. To which Green replied, “I think I’ll go with the old man.” And go with him he did, to Harpers Ferry, where after 18 hours, the insurrection ended with 90 marines under the command of Col. Robert E. Lee capturing Green along with Brown and others.

Green was tried, convicted and executed by hanging on Dec. 16, 1859, two weeks after Brown’s solemn trip to the gallows. He was not convicted of treason, however, since, under the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, only “citizens” could commit the crime and Blacks were not. Green’s remains were given to students at the medical college in Winchester for dissection. Shields Green, at 23, was the youngest of the five African Americans with John Brown. He left no survivors.

Years later, in 1881, Douglass was the commencement speaker at Storer College, founded on the hill above Harpers Ferry for formerly enslaved persons. He lavished praise on Brown, but also on Shields Green, whose bravery and courage he deemed exceptional. Should there ever be a monument in Harpers Ferry to Brown, he said, Green should have a prominent place on it.

One hundred and sixty-five years later, there is still no monument in Harpers Ferry to Brown or to Green, who had met for the first time in Rochester, New York, in February 1859.

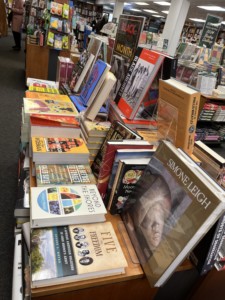

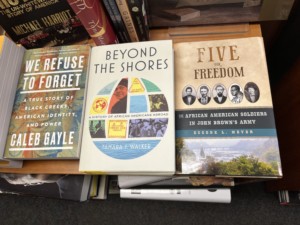

Five for Freedom was first published in June 2018, and I’ve been privileged to share the story some 40 times on Zoom and in person, as well as in its pages, which currently reside on the table reserved for Black History Month at Politics and Prose, the iconic Washington bookstore.

“Five for Freedom” on display at Politics and Prose

“Five for Freedom” in good company

“Eugene Meyer has given the story of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry new meaning and relevance by restoring Brown’s black collaborators to their rightful place in history. Five for Freedom elevates the names Newby, Anderson, Copeland, Learn, and Green to stand with Brown as individuals who were willing to sacrifice their own lives to rid our country of the horror of chattel slavery.” — MARGOT LEE SHETTERLY, author of Hidden Figures

What a beautiful posting.

Hi Gene,

Thanks for the wonderful work you’ve done on Mr. Brown’s black Harper’s Ferry raiders. This work is vital to the study of John Brown and is much appreciated, a new classic on the JB bookshelf. Brown’s legacy is much benefited by having a veteran journalist, researcher, and scholar like you bring your focus to bear on the story.