Hiroshima, the Enola Gay, Paul Tibbets and Me

December 7, 1941, was, declared President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “a date which will live in infamy,” when Japanese planes attacked and destroyed the U.S. naval fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor, resulting in the death of some 3,000 Americans.

Fast forward to Aug. 6, 1945. Eighty yeas ago, the Enola Gay B-29 Superfortress dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima. The first use of a nuclear weapon used in war killed an estimated 150,000 Japanese, mostly civilians? Was it — is it — another date which will live in infamy?

Many think so, although their assertions once loudly proclaimed are now more muted by time and the revelation of subsequent mass atrocities — the Holocaust, with a death count of 6 million Jews; the My-Li massacre in Vietnam, the fratricidal Rwanda genocide, the ethnic cleansing of Muslim citizens n the former Yugoslavia, and, some would add, the tens of thousands of deaths of innocents killed in the Israel-Gaza war.

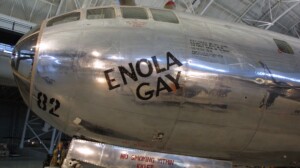

In 1994, anticipating the 50-year anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, followed by a second bomb dropped three days later on the city of Nagasaki, the Smithsonian Institution was preparing an exhibit marking the landmark birth of the atomic age. The 60-foot forward fuselage of the Enola Gay — named after the pilot’s mother – was to be the exhibit’s centerpiece in the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum on the National Mall.

This historic artifact was stored in a Smithsonian warehouse in nearby Suitland in Prince George’s County, Maryland. But it wasn’t the plane itself that was controversial, it was the script that Smithsonian staff had prepared to to accompany it.

The first hint of the controversy came in a Capitol Notebook column in The Washington Post, deep inside the front section, on May 31, 1994. It was a mixture of news and commentary, written by Guy Gugliotta, who predicted that “the museum will continue to have a difficult and perhaps impossible time presenting any atom bomb display that will satisfy the vets.” A month earlier, the editor of Air Force, the magazine of the 180,00-member Air Force Association, wrote that the exhibit, already under scrutiny by veterans, would have a “shock effect.” The disagreements until then were percolating under the surface. The America Legion also jumped into the fray.

The exhibit’s narrative, even after revisions, seemed to critics to impugn those who made and executed the fateful decision to drop the bomb, while ignoring or downplaying Japanese atrocities. It was explosive; many veterans and others were not pleased. Among them was Enola Gay pilot Gen. Paul W. Tibbets.

My recollection of how I came to this story is hazy; perhaps it was because my perch at The Washington Post was in Prince George’s. As the internal dispute mushroomed, I wrote the first of my 19 stores on the subject for The Post . Published on July 24, 1994, the story was buried on page C2 inside Metro. It carried the too-cute headline: “Dropping The Bomb; Smithsonian Exhibit Plan Detonates Controversy.” Most of my stories were in the Style section but burst onto the front page of the newspaper a few times in September 1994 and January and May 1995. The paper also carried op ed columns and editorials largely critical of the Smithsonian.

Tibbets refused to meet with the curators. But he did meet with me. In the midst of all this, we spent a day together (May 23, 1995), and he inscribed his paperback “Flight of the Enola Gay” to me after “a painless interview – With Best Wishes.”

I also traveled to Chicago to attend the 50th anniversary reunion of the 509th Composite Group, the unit that that prepared the bomb runs and included the crews of the Enola Gay and Bock’s Car (after its pilot Fred Bock) that dropped the second bomb three days later on Nagasaki. On a bus ride, we went to the University of Chicago, where physicists had worked on the science that led to the bomb.

There was no discussion to which I was party on the morality of the bombings. In their minds, it was a means to an end–the end of World War II, possibly saving up to one million American lives, and likely as many Japanese, had the United States proceeded with the planned November 1945 land invasion of the Japanese home island. Of course those numbers were and still are disputed. I wrote and sent the story from a high-floor hotel room overlooking Lake Michigan one afternoon, and it was the Style front feature the following day.

The controversy was so radioactive that Martin Harwit, the Air and Space Museum director, resigned in May 1995, and the exhibit script was scuttled. Instead, the fuselage would be displayed without any interpretation–some would say without context. Ultimately, the wartime relic was moved to the Smithsonian’s airplane Uhar-Hazy Center near Dulles International Airport, where it remains today.

The stories generated many letters to the editor and published criticisms of our coverage elsewhere, notably in the D.C. City Paper and the American Journalism Review, and even spawned post-mortem books. I’d previously been denounced in Congress by no lesser persons than Senators George McGovern, High Scott and Ed Brooke — for my profiles or stories. It goes with the territory. But this time it was different. My atomic critics included some I might normally, at least privately, align myself with.

The critics accused the Post and me personally of biased reporting, by sins of omission or commission, allegedly slanting our reporting and editing against the historical revisionists. Among them were Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, who would years later write the American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, which won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for Biography and was the basis for the 2023 “Oppenheimer” bio-pic that garnered seven Academy Awards.

On April 28, 1995, Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin — as Co-Chairs of Historians’ Committee for Open Debate on Hiroshima — wrote a letter to six masthead names at the Post (Don Graham, Leonard Downie, Robert Kaiser, Karen DeYoung, Meg Greenfield &JoAnn Byrd). Copying me and Style writer Ken Ringle, who’d written a commentary with a clear point of view, they asked for “a meeting at your convenience.” On the copy Kai sent me, he wrote in pen at the top: “Gene, you know we have been unhappy with the Post’s coverage. I wish it could be otherwise. Please feel free to call me to discuss this. Kai.”

Their letter, they wrote, was “to draw your attention to what we believe has been an unfortunate and extended episode of biased, unbalanced and inaccurate coverage of the Enola Gay controversy at the Smithsonian Institution.” They attached a 12-page single-spaced rebuttal, criticizing Post editorials and editorial columns, Ringle’s analysis, and several of my stories, including the Tibbets profile, describing it as “an admiring profile…full of invective against ‘revisionist’ arguments’ and makes no attempt to balance its admiring portrait of an admittedly likeable guy with any questions about his obviously questionable view of historical events.”

Whatever disagreements I had with Kai were civil, and today, we are passingly friendly, as he is a major figure in the Biographers International Organization, to which we both belong and which bestowed on him its 2024 Bio Award “for his significant contributions to the art and craft of biography.”

Unwittingly, and regrettably in hindsight, my coverage and I became part of the story. It did not help matters when I agreed to write an essay for The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists in its November-December 1994 issue that invited further criticism. Headlined “Revisionism, revised,” it was called a “Guest Opinion.” I did not undertake it without the express approval of my Style editors, but still. I think now it was a mistake.

Scrolling through the many script revisions, I found “a shift toward balance…Gone are most of the leading questions, by and large, the facts are left to speak for themselves. Enough vivid images of the atomic aftermath remain to make the point, but there is more context… [D]espite the death and destruction wrought by the atomic bomb, it may also have been a life-saver. and saving American lives was, after all, the principal mission of both the Enola Gay and Bock’s car…With the swift end of World War II, the mission was accomplished.” My rather benign, it seemed to me, conclusion: “Whether the means used to accomplish that mission were moral or immoral is a question that all of us may wrestle with–preferably without a prepacked answer.”

Even though I thought I was being even-handed, I was just throwing more fuel on the flames. The flames died out after the stripped down Enola Gay was moved to the Smithsonian’s huge display hanger Uhar-Hazy near Dulles International Airport, where it may be viewed. with only technical information added to inform visitors,

After the fuselage was thus sequestered, out of sight if not out of mind, I was asked to moderate a panel at the 2023 Washington Writers Conference. The subject was “Politics and History: Even Nonfiction Needs a “Story,” and the panelists were David Stewart, Elliot Ackerman, and Evan Thomas, the grandson of socialist and pacifist Norman Thomas and a distinguished journalist and author in his own right. In preparation for the panel, I read all three books but with a personal interest in Thomas’s volume, Road to Surrender: Three Men and the Countdown to the End of World War II. I’d sent him a copy of my Bulletin article. His thesis, barely contested in the public square upon its publication, focused on three men — Secretary of War Henry Stimpson, Air Force Commander Carl Spaatz and Japanese Foreign Minister Shigenori Togo — and concluded that the Japanese, absent the bombings, would not surrender, reinforcing the traditional narrative.

The panel, of course, was not all about him or the Second World War, and we had a good discussion on the craft of telling a story when writing history. I had with me my paperback advanced readers copy of Road to Surrender, with the usual “not for sale” warning. So sell it I did not. But I did ask the author to sign it. On the title page, he wrote, “To Gene Meyer who knows a lot about this subject!” How times change. Road to Surrender did not generate much if any controversy. On Amazon, it received 1,231 mostly five-star ratings. NPR named it a “best book of the year.”

Enter Trump 2.0. Federal agencies have been ordered to scour their websites and purge anything vaguely related to his interpretation of “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.” Apparently relying on a search algorithm, in a spasm of thoughtless censorship, the Enola Gay was deleted from the Defense Department website. The name Gay of course being the “trigger” word. Silly, but also ominous. After the deletion was publicized, the Enola Gay was restored to the DOD site.

Postscript: The Air and Space Museum is preparing a new exhibit on the mall. The subject is “World War II in the Air,” and it is schedule to open next July. The museum has listed a number of aircraft to be displayed. Will the story of the Enola Gay, Bock’s Car, and the 1994-1995 debate over the decision to drop the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki be included? Don’t bet on it.

Meanwhile, The Washington Post reported that Donald Trump’s name was removed in July from a “temporary” exhibit on presidents who have faced impeachment, though he was twice impeached. Now the exhibit says that “only three presidents,” Andrew Johnson, Bill Clinton and Richard Nixon, “have seriously faced removal.” The Post story notes that “the change coincides with broader concerns about political interference at the Smithsonian and how the institution charged with preserving American history could be shaped by the Trump administration’s efforts to exert more control over its work.” After an public outcry, the Smithsonian has said it would restore Trump’s name and his two impeachments to the display “in the coming weeks.”

In another affront to history, the National Park Service announced it is repairing and returning the statue of C0nfederate Brigadier Gen. Albert Pike, alleged to have been a Ku Klux Klan official, to its former perch off Pennsylvania Avenue NW a mile east of the White House. In 2020, at the height of the Black Lives Matter and George Floyd protests, angry citizens pulled the statue from its pedestal. He was the only Confederate leader memorialized with an outdoor statue in our nation’s capital.

By taking up arms against the Union, Pike committed treason, and, afterward championed the Lost Cause. The Boston-born Pike moved to Arkansas in 1833 and joined the anti-Catholic Know Nothing Party but walked out of its national convention in 1856 because it did not adopt a pro-slavery platform. In 1858, he signed a petition to expel free Blacks from Arkansas. After the war, he opposed giving Blacks the right to vote. He wrote in 1868 in a Memphis newspaper that he approved of the Klan’s aims, just not its methods or leadership. Recently, The Post reported: “Pike’s return comes during the Trump administration’s wider campaign to scrub federal institutions of ‘corrosive ideology’ recognizing historical racism and sexism.”

–

In some other news, old and new:

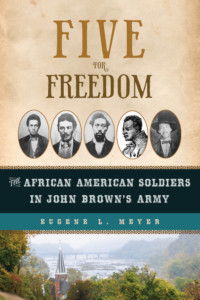

My book Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army remains relevant more than eight years after its publication in June 2018. The men I write about died to make us free. As evidenced in today’s headlines, when we are daily facing new threats to our democracy, the struggle continues. In February 2023, I gave a Zoom presentation on the subject for the Montgomery County Historical Society (rebranded as Montgomery History). To watch it, please click here. To purchase a copy, click here.

Finally, I am pleased to have been featured in a Member Interview in the July issue of the The Biographers Craft discussing my current work-in-progress, a biography of the musical polymath and my cousin Andre Previn, and how I handle the many challenges facing a biographer. To read it, click here.

Fascinating history and insights. Thanks for posting. I was nearly 8 years old when the bomb and still remember hearing the announcement on the radio and then my father, a production engineer for the B 24 bomber, trying to explain to me what he knew about how the bomb worked. It was my first introduction to physics. More important, I remember how relived my parents and their friends were because they had cousins and knew men who were serving in the Pacific campaign. They were glad the Japanese surrendered, and a costly invasion was avoided.

Amazing story, Gene-O. . . . Well told.

Your writing is a true testament to your expertise and dedication to your craft. I’m continually impressed by the depth of your knowledge and the clarity of your explanations. Keep up the phenomenal work!