Harriet Newby’s “One Bright Hope”

“I want you to buy me as soon as possible, for if you do not get me some body else will,” Harriet, an enslaved house servant, wrote on this day in history, Aug. 16, in 1859, to Dangerfield Newby with whom she had as many as seven children and an enduring union in the slave state of Virginia.

Addressing her letter to “Dear Husband” and signing it “Your affectionate wife,” she declared, not for the first time, that “their has ben one bright hope to cheer me in all my troubles that is to be with you…”

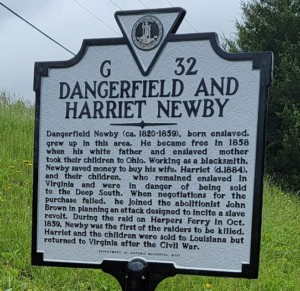

Dangerfield had been born enslaved in 1820 to Henry Newby, a white man who was also an enslaver, and Elsey Pollard, a Black woman held in bondage by John Fox, who enslaved as many as 193 people on his sprawling plantations in the Piedmont of Virginia. The majority living there then were enslaved. Dangerfield had been among them. Born in 1820, he was the oldest of Henry and Elsey’s 11 children. In 1858, Fox allowed them to move to the free state of Ohio, where they would by law become free. Three of Dangerfield’s brothers served in the Union army; one died from a wound in April 1864. Four months later, Elsey, 64 years old and living in Bridgeton, Ohio, filed a “Mother’s Declaration” for an army pension. In her application, she attested that she and Henry had been married in 1818, two years before Dangerfield’s birth.

Dangerfield was a blacksmith. In Ohio, he continued to ply his trade and save money to purchase Harriet and their children before their slaveholder, Dr. Lewis Jennings in Brentsville, then the Prince Williams County seat, could sell them “down the river” to the cotton plantations in the deep south, where life was much harsher for enslaved people.

Jennings was facing financial hard times when Dangerfield sought to negotiate their release. He had amassed $21,000 in today’s dollars, not enough, it seemed, to clinch the deal. Then, Dangerfield met John Brown, the fiery abolitionist who was recruiting African Americans to join in his ultimately ill-fated raid on Harper’s Ferry, with its federal armory and arsenal and rifle works, at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers. There he hoped to incite a slave insurrection that would topple the hated institution of slavery.

Dangerfield was a willing recruit.

From Brentsville, Harriet wrote to him three times–on April 11, April 22, and Aug. 16. In the first, Harriet reported that “Mrs. gennings,” her master’s wife, had been sick after giving birth to a baby girl. Harriett had to stay with her “day and night.” Their own children were all well. “I want to see you very much…Oh, Dear Dangerfield, come this fall without fail, money or no money. I want to see you so much. That is one bright hope I have before me.”

Harriett received a letter back on April 22 and responded the same day: “Dear Dangerfield, you cannot imagine how much I want to see you. Com as soon as you can, for nothing would give more pleasure than to see you. It is the grates Comfort I have is thinking of the promist time when you will be here. Oh, that bless hour when I shall see you once more.”

Dangerfield would carry these letters with him to the farmhouse where Brown’s raiders assembled and prepared for their futile assault. Of special interest to him was Article 42 of Brown’s provisional constitution for the free republic he hoped to establish. Ratified in May 1858 in Chatham, Ontario, it said:

The marriage relations shall at all times be respected and families kept together, as far as possible, and broken families encouraged to unite, and intelligence offices established for this purpose.”

Not so with the federal separation policy under Trump, until rescinded, and now revived by Republican Texas Gov. Greg Abbott.

Plaintively, Dangerfield would ask John Brown when he could respond to Harriet’s letter. “Soon, Dangerfield, soon,” Brown would tell him. Dangerfield could not foresee the future. He could still hope, but only misery lay ahead.

Brown’s raiders were able to seize the unsuspecting town, arsenal and rifle works on the evening of Oct. 16, 1859, but the next day his plan began to unravel. Local militias arrived; eventually, 90 marines led by Col. Robert E. Lee would storm the arsenal fire engine house, where several of Brown’s men had retreated with hostages.

Newby, stationed at the entrance to the Shenandoah River bridge, crossed an open area in an attempt to join his captain. There he was gunned down by a sniper who shot a six-inch railroad spike across his throat. Angered townspeople quickly began dismembering the dead man, and then they left him for the hogs, who routed about his remains. Newby’s body lay in the street for a day and a half before being removed and buried in a shallow grave a half mile upriver.

In 1860, Harriet and the children were sold south to a Louisiana planter. Union forces soon occupied the region, and they wound up in a camp for “contrabands,” where she met William Robinson, a soldier in the U.S. Colored Troops, whom she married. After the war, they returned to Virginia, where she had three more children with her second husband, a prosperous farmer in Fairfax County, near Mount Vernon. She died in 1884, but she had many survivors, and their descendants still live in the area, as close as Warrenton, the seat of Fauquier County, as far away as Portland, Oregon, and Cannonville, Utah.

Dangerfield and Harriet Newby were then forgotten, hidden figures, their tragic love story barely a footnote to the John Brown episode.

As I wrote my book Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army, I visited the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the Mall. There was one reference to the Newby tragedy. In a section about families being torn asunder, I found a single sentence, inscribed on a plaque, from Harriet Newby to Dangerfield declaring him her “one bright hope.” But there was no context, nothing about Dangerfield’s role in the John Brown raid.

In Five for Freedom, I devote an entire chapter titled “One Bright Hope” to the story of Harriet and Dangerfield Newby. In subsequent chapters, I write about their descendants down to the present time, living lives of achievement while grappling with racism and their bi-racial heritage.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Five for Freedom was published in June 2018. For Black History Month in 2020, Virginia fourth graders were invited to nominate largely forgotten African Americans to be memorialized on state highway plaques. A Fairfax County teacher, using my book as an educational resource, told her students about Harriet and Dangerfield, and they nominated them for one of the plaques. Finally, in May 2022 the plaque was erected in northwestern Culpeper County, in the area where Dangerfield had been born.

Thankfully, and belatedly, Harriet and Dangerfield Newby are hidden figures no more.

Very good Gene

Such a painful story but one that people need to know. Thank you Gene for sharing and reporting.

Gene, it hurts to think that this story and your book might be banned on some schools. I admire you greatly for the work you do.